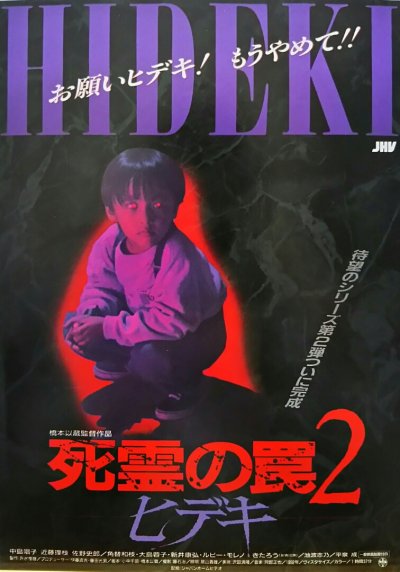

Love & Pop

(contains Spoilers beware!)

I've been meaning to watch this Hideaki Anno live action film from 1998 for ages and finally got around to it. A day in the life of worldly sixteen year old Hiromi that descends into a dark odyssey to buy an expensive topaz ring that's on sale before the store closes for the night. I thought it was pretty excellent. While it's in a completely different medium and lacking any mecha, I'd say it's a great companion piece to Evangelion, it shares many similar angsty themes of alienated teenagers learning how to grapple with a world that seems to be falling apart and infested with corrupted coercive adults, and trying to become an adult yourself in that world, but showing this from a female perspective. I suppose some might say the big difference is that Hiromi doesn't have some big burden thrust on her like Shinji did and rather she chooses to burden herself with an inordinate desire to buy a fancy ring. But where do such desires arise? I think that sells short the power and immediacy of the consumerist thirst late-stage capitalist societies can implant in us. To a sixteen year old who has had their perspective on life warped and narrowed or at least not allowed to expand naturally, getting a ring probably can seem like an existential crisis on a par with the impending destruction of the world. And I think for me, the point of this film kind of is who needs Angels to destroy society when it's already collapsing under the weight of our own fragmented self-obsessed lives. The Tokyo depicted in Eva is in so many ways more desirable than the grimey one shown here.

The film perhaps could be accused of defaulting to notions of girls being materialistic and money hungry, and it certainly feeds into and capitalises off of the whole enjo kōsai moral panic of 90s Japan. But that kind of misses the point. I think it's clear the film's intention isn't to criticise or judge these girls, its real target is capitalism and the hyper-consumer culture that has so warped society. To drive this home we even get POV shots from the perspective of various objects, like model trains or the yearned for ring, objectifying the humans. Obviously the girls are the most obvious example in the film of people turning themselves into commodities to get the objects of their desire, by basically been teenage escorts for creeps, but I think the implication is that we're all doing it, we're all debasing ourselves awfully and leading narrow solipsistic lives. After all, these supposedly debased girls are the only ones in the film who actually show much kindness, consideration and any sense of community and solidarity, while the rest of the world either preys on them or turns a blind eye to the predation.

The film very directly speaks to the problem of immediacy in modern society, the girls don't seem to have much of a sense of the future, there's only the here and now. Obviously a part of this comes with the territory of being a hormone fuelled teenager, but I think it also speaks of something broader going on in society too. One of Hiromi's friends decides to drop out of school to pursue a career as a dancer because she's worried if she doesn't do it immediately a new impulse will carry her away or the desire will just fizzle out by itself. Hiromi agrees and feels an urgency to get the topaz ring of her dreams today in case her ambition and lust deserts her tomorrow, she can't wait or save up, she has to do whatever it takes to get it today. And she desperately tries to capture as many fleeting moments as she can on camera along the way, maybe because she isn't sure they'll be anything worth capturing tomorrow or will be a tomorrow at all. It's FOMO writ large. At times it almost seems questionable as to how much Hiromi even truly wants or cares about the ring, almost as if a lust for some immediate tangible object is a pre-requisite to feel alive and capture the present. All the while the camera and editing seems to mirror this struggle to stay grounded and gain perspective, there are some really nice longer shots, but there's a so much disorienting rapid flitting around of angle and perspective, overlaying and distortion.

The men (there are no teenage boys here, except for off screen boyfriends who sound as selfish and disappointing as everyone else) are almost uniformly shown to be absolutely broken and irredeemably predatory. At best there's Hiromi's father who is presented as a nice-enough but entirely absent individual who misses her phone calls when she's in need because he's glued to his model train set all day. Hiromi and her friends can seemingly not walk down a street without having some creep accost them brazenly and beg to pay them for their time. And the speed at which the men can go from pitiful and eccentric to shockingly violent genuinely caught me off guard. The film also comments on the way that men like to lecture girls about their lack of decency while simultaneously being the very ones who are debasing them; there's an early customer who accosts them for a meal and proceeds to angrily lecture them on how they're wasting their lives after gloating about his own daughter. And most grotesquely ironic of all is how the chastising words of Tadanobu Asano's Captain EO obsessed violent monster of a punter (the very words he uses to justify his violence) get interpreted by another man as the life-affirming advice only a kind soul can give about knowing your self worth.

And the end of it all and without even the ring show for it, Hiromi comes to the realisation that in order to move forwards in her life she needs to be able let go of both the present and whatever unattainable desires are holding her back. Even if she's not sure she's up to the task, and the film doesn't present any obvious path ahead, there's the hope she might be able to wade forwards, become an adult and find some inner peace.

Also a side note, but watching this film it really struck me just how much of its style the Monogatari series got from Anno's work. The editing, the angles, the frames of text the rapid fire dialogue, it's all here. It never really hit before, I guess it's because in Love & Pop those elements are dialled up so much further than in Eva, so stylistically, if not thematically, it resembles Monogatari much more obviously.