You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rate the Last Film You Watched

- Thread starter Professor Irony

- Start date

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

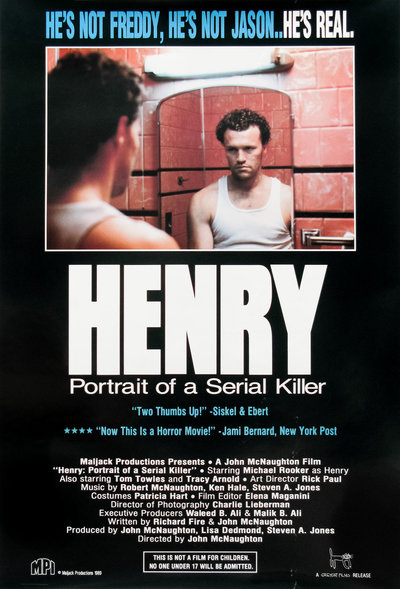

Day XVI: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986, John McNaughton)

A clinical and unflinching insight into the life of a serial killer and the company he keeps, with tragedy ensuing when a failed romance enters the picture. The realism of the overall story gives the film its edge and the the gore is fairly minimal and impactful when it does appear. 5/5

Day XVI: Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986, John McNaughton)

A clinical and unflinching insight into the life of a serial killer and the company he keeps, with tragedy ensuing when a failed romance enters the picture. The realism of the overall story gives the film its edge and the the gore is fairly minimal and impactful when it does appear. 5/5

RadFemHedonist

Guild Member

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

Day XVII: Prom Night (1980, Paul Lynch)

A slasher that takes its time to get going but was still a decent watch, even if Leslie Nielsen isn’t in it enough. 3/5

Bullet for the General (1967)

The first in a cycle of Italian westerns set during the Mexican Revolution, I was pleasantly surprised by this one. Gian Maria Volonte (probably best known now as the baddie in the first two Dollars films) stars as a seemingly ambivalent bandit leader who makes a living stealing guns from the army to sell to the revolutionaries, only to have his smash and grab lifestyle called into question after he befriends a shifty American dandy (Lou Castel) who helps him raid a train.

I really only expected a trashy shoot-em-up about a train robbery, maybe with some eye-rolling from co-star Klaus Kinski (!) as additional flavour, but this is an unusually humane and thoughtful (at least as spaghetti westerns go), character-driven piece, with a tremendous turn from Volonte as a man forced to confront his own horrible reflection.

It lacks the visual flair of Sergio Leone’s films, something most noticeable during the flatly shot action scenes, and the ‘twist’ is rather obviously telegraphed right from the start, but the strength of the performances kept me glued to the screen all the way along.

The first in a cycle of Italian westerns set during the Mexican Revolution, I was pleasantly surprised by this one. Gian Maria Volonte (probably best known now as the baddie in the first two Dollars films) stars as a seemingly ambivalent bandit leader who makes a living stealing guns from the army to sell to the revolutionaries, only to have his smash and grab lifestyle called into question after he befriends a shifty American dandy (Lou Castel) who helps him raid a train.

I really only expected a trashy shoot-em-up about a train robbery, maybe with some eye-rolling from co-star Klaus Kinski (!) as additional flavour, but this is an unusually humane and thoughtful (at least as spaghetti westerns go), character-driven piece, with a tremendous turn from Volonte as a man forced to confront his own horrible reflection.

It lacks the visual flair of Sergio Leone’s films, something most noticeable during the flatly shot action scenes, and the ‘twist’ is rather obviously telegraphed right from the start, but the strength of the performances kept me glued to the screen all the way along.

Yami

Thousand Master

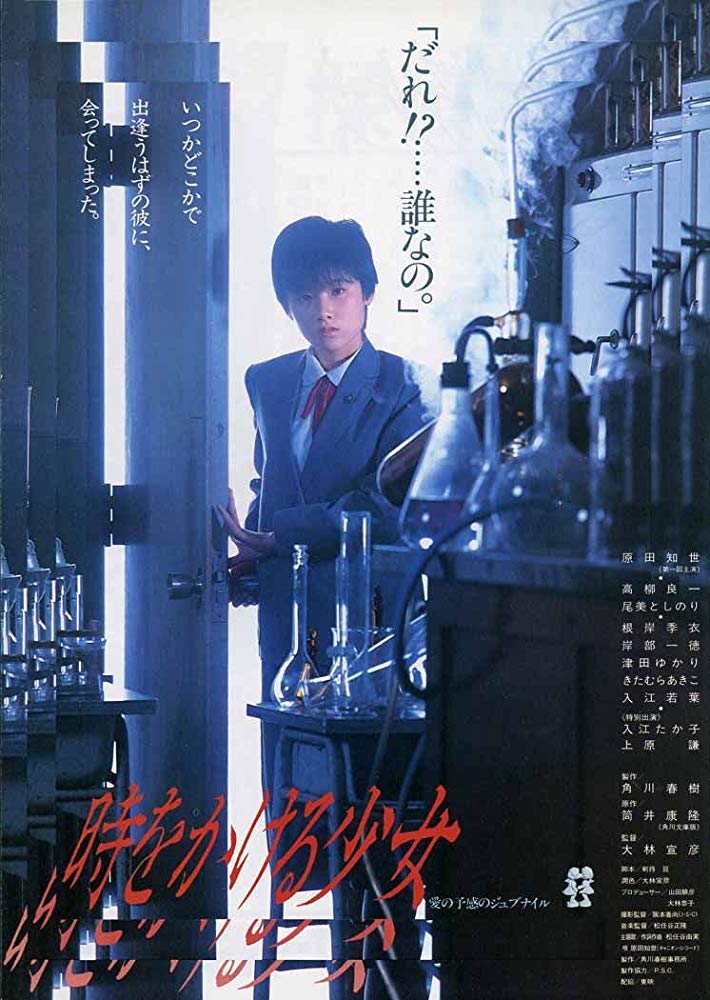

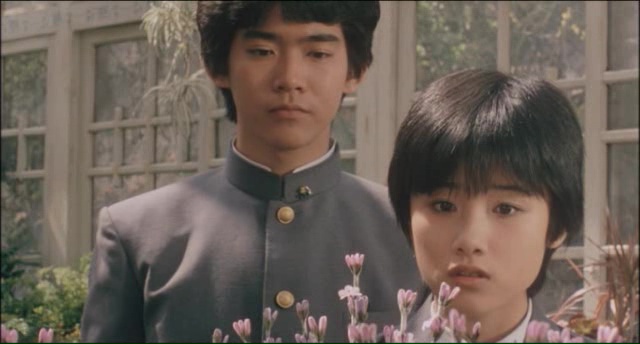

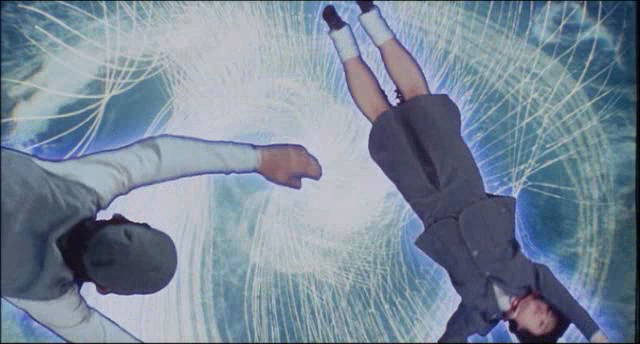

One of Obayashi’s most popular films in his homeland, The Girl Who Leapt Through Time was voted as one of the top 100 Japanese films ever made in the most recent Kinema Junpo poll. The middle film in his ‘Onomichi Trilogy’ of films set in his hometown, it is based upon an early novel by Yasutaka Tsutsui which was also later adapted into an animated film of the same name by Mamoru Hosoda.

From what I gather, the film was produced as a vehicle for upcoming idol Tomoyo Harada who, at that point, was the lead in the TV series adaptation of Sailor Suit and Machine Gun which had earlier been a massive hit as a theatrical feature directed by Shinji Somai that launched the career of Hiroko Yakushimaru. Yakushimaru also starred in Detective Story, the film that was double billed with The Girl Who Leapt Through Time on original release. Harada would go on to a successful singing career, as well as working with Obayashi on The Island Closest to Heaven (also included in this set), Samurai Kids, Goodbye for Tomorrow, and as lead voice actress on his lone anime Kenya Boy. She would also narrate the 1997 version/60s-set prequel of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time directed by Haruki Kadokawa, who personally funded the original Obayashi film and as then-president of Kadokawa was instrumental in launching her career. Kadokawa directed the film after being released from jail, where he was serving time for drug smuggling and embezzlement. Anyway…

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time foregrounds some of the themes that would occupy Obayashi for his entire career, most obviously that of the non-linearity of time; as Faulkner famously wrote in Requiem for a Nun, “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” In the work of Obayashi, characters and communities forever struggle to escape from the past – and to understand it. From House to his War Trilogy, he spent his career illustrating how the past, whether personal or impersonal, exerts influence on the relationships and actions of his characters in the present day.

In The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, “time isn’t the past, it’s the future” as schoolgirl Kazuko finds herself reliving the same day after a lavender-related laboratory accident. In comparison to other Obayashi films, time is something more tangible in this film – a dimension through which characters can travel – but nevertheless, the principle is largely the same as is best summed up in the final couple of scenes.

The film directly ties Kazuko’s slightly-wibbly-wobbly-timey-wimey experience to puberty and coming-of-age, anchoring the fantastic in a relatable narrative of first love - the heady rush of hormones and confusingly new emotions.

I think that Obayashi’s distinctive visual style really came of age in this film, with his use of both black-and-white and colour photography being influenced by not only The Wizard of Oz (a poster of which is present in Kazuko’s bedroom) but, perhaps more overtly, by Otto Preminger’s Bonjour Tristesse. Despite being famed for his wacky, sometimes incongruous, visuals, Obayashi’s aesthetic has always been in service to his thematic concerns and the time travel scene, perhaps the centrepiece of the film, uses optical effects, still photographs, multiple exposures, time lapse photography and other techniques that draw on Obayashi’s background in experimental shorts and make it perhaps the most interesting depiction of travel this side of Marker’s La jetee.

Given the popularity of Obayashi’s House and Hosoda’s anime version of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time, I’m surprised that it has taken so long for this film to get a release outside of Japan. It’s one of his most purely enjoyable works – romantic and sincerely sentimental but not cloyingly so, wrapped up in a lo-fi sci-fi package with a splash of pastel colours and a touch of early MTV that so defined the 80s idol movie. Alongside Somai’s Sailor Suit and Machine Gun, it might be the best of them.

B

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

With his second vehicle for idol Tomoyo Harada, Obayashi takes us to the picturesque shores of New Caledonia in search of the utopian ‘island closest to heaven’ vividly described to young Mari (Harada) by her recently deceased father. Will she find the ideal that she imagined she was looking for? More? Less? Maybe the important thing will be the friends she makes along her way?

There are interesting aspects to the film – the opening and closing credits are pure classical Hollywood and the visuals are beautiful (and the resulting increase in tourism to New Caledonia is hardly surprising) but I felt like there wasn’t much below the surface that Obayashi didn’t go onto revisit with greater complexity and more deft in later features – particularly in Chizuko’s Younger Sister, where Mika also comes of age under the weight of great loss but has to navigate the shadow of that ghost to affirm her own identity. In The Island Closest to Heaven, Mari's wistfulness makes way to an aimlessness and, ultimately, what feels like a pointlessness unless you want to spend 90 minutes with views of the beach.

C

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The other 'island' film in Third Window's 80s Obayashi set is more than worth the price of admission. His Motorbike, Her Island was one of two films that Obayashi released in 1986, the other being Bound for the Fields, the Mountains, and the Seacoast - an incredible one-two a la Francis Ford Coppola in '74 or Godard in '64 (or '65!).

Riki Takeuchi makes his film debut (he would also have a smaller role in Bound for the Fields...) as a young biker who takes a trip out of the city to clear his head after a break-up. There he meets Kiwako Harada (younger sister of Tomoyo, idol star of The Girl Who Leapt Through Time and The Island Closest to Heaven), who plays a young islander that quickly develops a crush on him - and moreso the motorcycle and the biker life.

It was adapted from a novel by Yoshio Kataoka that, to my knowledge, has never been translated to English but opens with the quote "Summer is more than just a season; it's a state of mind" - a play on the opening line of Samuel Ullman's poem Youth, well known in Japan as a favourite of Gen. MacArthur's. I think that Obayashi's film carries a similar tone - it's not as obviously counter-cultural as other biker / bōsōzoku films like Yanagimachi's God Speed You! Black Emperor or Ishii's Crazy Thunder Road or even, say, Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider but it nevertheless has a cheeky irreverence.

And, like all great summers of youth, the memories they make are idealised distortions of reality. Obayashi's interchanging of black-and-white and colour film is, in this film, most clearly purposeful and effective - mirroring the variability of memories: the vibrancy, intensity and accuracy of the remembered image and how that relates to the affect of the character(s) at the time.

"I'll be a motorbike, you'll be an island and together we'll be the wind!"

His Motorbike, Her Island is one of the most romantic films ever made but not only is it a romance between two young bikers, it's a romance between them and the ideal of freedom. The freedom of the wind, forever changing direction and exploring new corners of the horizon. A freedom enabled and emboldened by technology and the Japanese economic miracle. A freedom made possible by peace and a generation unburdened by wartime responsibility. A freedom that is, nevertheless, fragile with unknowns around the next bend in the road.

It's a wonderful, wonderful, wonderful film - one of the best of the 1980s and one of the best of Obayashi's career. I've seen it a few times now and every time it's like a breath of fresh air, one of the most purely enjoyable films ever made.

A

Dai

Combat Butler

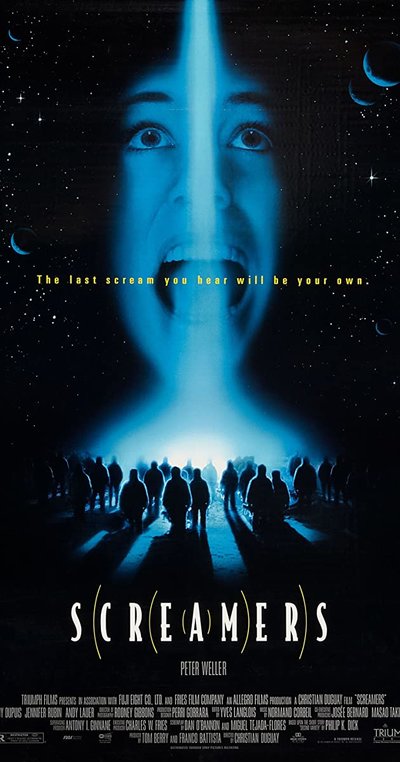

Yeah, when this came out I recall being excited to see Peter Weller in a sci-fi movie again after Robocop, but it was just meh. The twist didn't work either; it somehow managed to make things less interesting.A sci-fi horror film based on Philip K. Dick’s short story “Second Story” with Peter Weller as the lead. There’s some rather eerie imagery to be had here but I found the film overall to be middling. 3/5

Weller really carries the film but sadly couldn’t elevate it above its average execution.Yeah, when this came out I recall being excited to see Peter Weller in a sci-fi movie again after Robocop, but it was just meh. The twist didn't work either; it somehow managed to make things less interesting.

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

Day XIX: Poltergeist (1982, Tobe Hooper)

A classic horror film that surprisingly got a PG rating back in the day, and sports some great performances including from Heather O’Rourke, who sadly passed away before the release of the third film in the series. The new UHD release for this is great too. 4/5

Day XIX: Poltergeist (1982, Tobe Hooper)

A classic horror film that surprisingly got a PG rating back in the day, and sports some great performances including from Heather O’Rourke, who sadly passed away before the release of the third film in the series. The new UHD release for this is great too. 4/5

jake scully

Kiznaiver

Yes in the USA producer Spielberg - although there are some stories going round he directed more scenes than director and Tobe Hooper - he appealed to the US censors MPAA for the PG rating than the R rating which was originally given and of course he won but over here a 15 and to be honest in my opinion not a classic by any means

jake scully

Kiznaiver

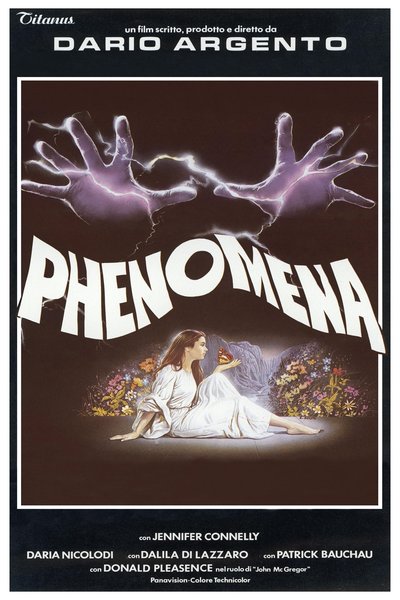

Already got the earlier blu ray of Phenomena with Monkey Business extra but bought the blu ray with commentary and Of Flies And Maggots doc which is over 2 hours - longer than film31 Days of Halloween 2022!

Day XV: Dario Argento’s Phenonema (1985, Dario Argento)

View attachment 26571

A more supernatural-oriented horror from Argento, this eccentric thriller stars Jennifer Connelly & Donald Pleasance who do solid work with their roles. 3.5/5

- not Argento best film but still really enjoyable

Eternal chibi

Student Council President

I watched The Devils by Ken Russell and expected a horror and instead got a true story of a 17th century priest gigachad that got so many girls he enraged the town

Weird as hell cos it's Ken Russell, he brings some rock & roll to the renaissance. This was heavily censored upon release because of the sex and violence.

The show was completely stolen by the great supporting cast who were clearly allowed to have a lot of fun with their parts. Highly recommend.

Weird as hell cos it's Ken Russell, he brings some rock & roll to the renaissance. This was heavily censored upon release because of the sex and violence.

The show was completely stolen by the great supporting cast who were clearly allowed to have a lot of fun with their parts. Highly recommend.

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

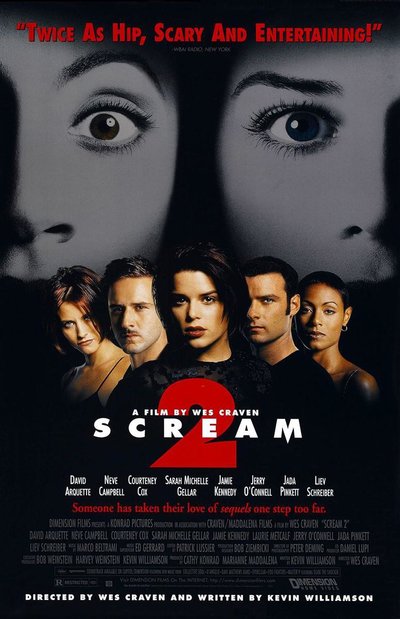

Day XXI: Scream 2 (1997, Wes Craven) & Scream 3 (2000, Wes Craven)

The first two sequels to Wes Craven’s self-aware slasher comeback Scream, these films offer satirical takes on slasher and horror sequels with S2 being a very good sequel and S3 being the weakest of the original trilogy. I will eventually check out Scream 4 and the recent Scream entry - maybe during next year’s marathon. 4/5, 3/5

Day XXI: Scream 2 (1997, Wes Craven) & Scream 3 (2000, Wes Craven)

The first two sequels to Wes Craven’s self-aware slasher comeback Scream, these films offer satirical takes on slasher and horror sequels with S2 being a very good sequel and S3 being the weakest of the original trilogy. I will eventually check out Scream 4 and the recent Scream entry - maybe during next year’s marathon. 4/5, 3/5

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

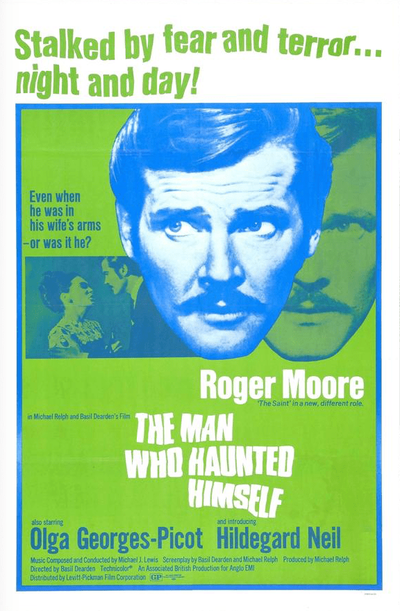

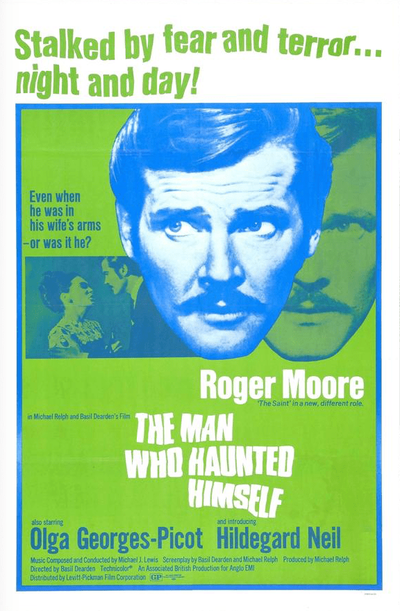

Day XXIII: The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970, Basil Dearden)

A standout performance for Roger Moore and his own personal best, this film hinges on Moore’s winning depiction of a man at odds, seemingly with a doppelgänger who interferes with his personal and professional life. 4/5

Day XXIII: The Man Who Haunted Himself (1970, Basil Dearden)

A standout performance for Roger Moore and his own personal best, this film hinges on Moore’s winning depiction of a man at odds, seemingly with a doppelgänger who interferes with his personal and professional life. 4/5

31 Days of Halloween 2022!

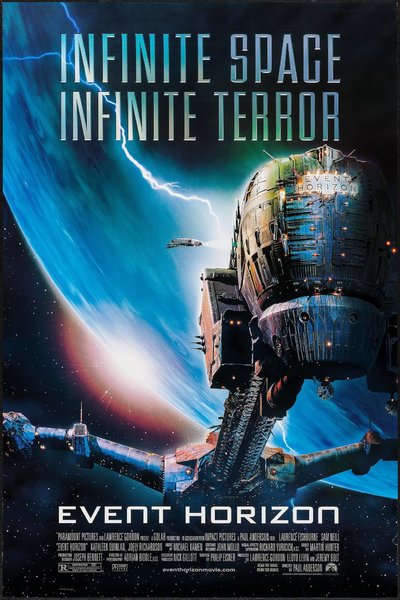

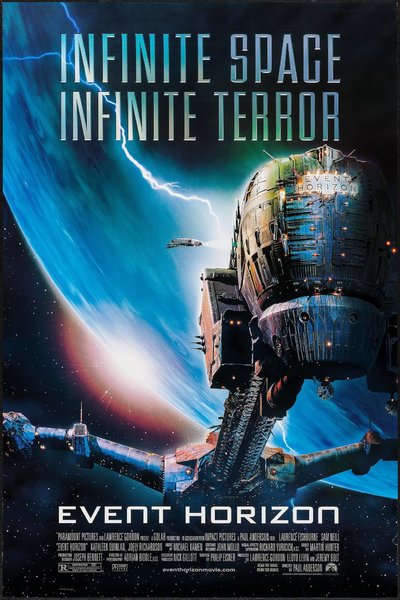

Day XXV: Event Horizon (1997, Paul W. S. Anderson)

A film deemed too graphic in its original cut, resulting in 30ish minutes of content being removed for theatres, with numerous scenes and sequences that are now considered lost media. EH is a solid film at its core with some great actors making up the cast but the glimpses into what could have been without censoring leaves me wanting more. 3.5/5

Day XXV: Event Horizon (1997, Paul W. S. Anderson)

A film deemed too graphic in its original cut, resulting in 30ish minutes of content being removed for theatres, with numerous scenes and sequences that are now considered lost media. EH is a solid film at its core with some great actors making up the cast but the glimpses into what could have been without censoring leaves me wanting more. 3.5/5