D

darkstorm

Guest

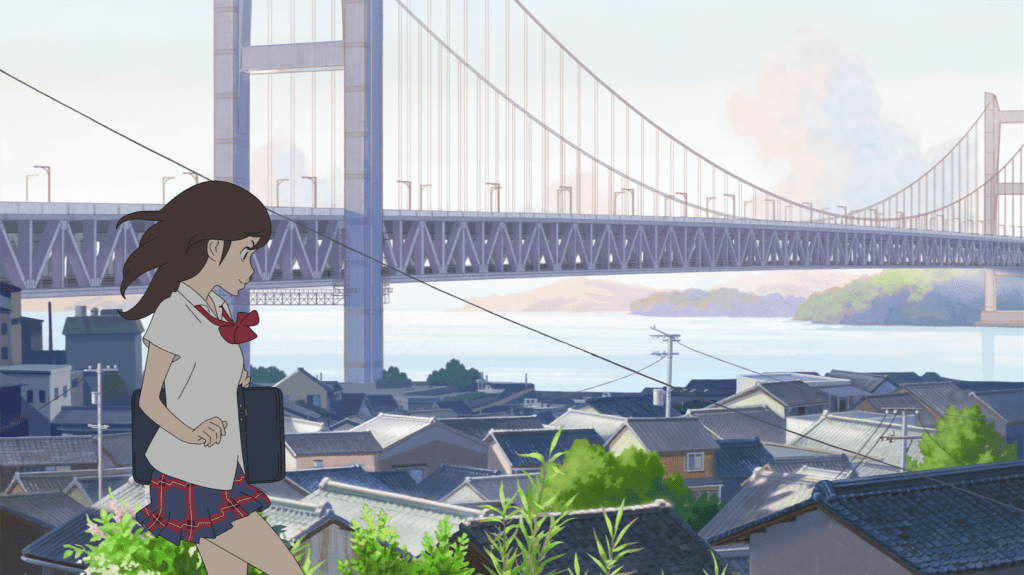

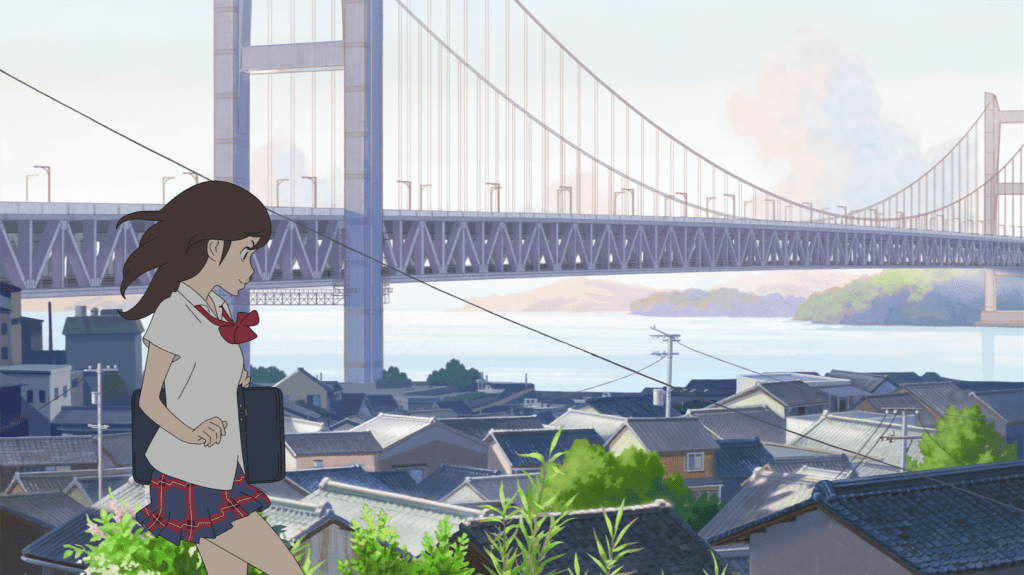

Kokone’s life is very simple; she lives in the country and is supposed to be preparing for a summer-long study session for entrance exams, but instead she spends a lot of time sleeping, even during class. Her world is turned upside down however when her beloved father is suddenly taken in by the police and accused of theft by a huge car company based in Tokyo. Desperate to find him, she enlists her childhood friend Morio to help, but as they journey across the country she finds out that her dream-filled sleeps may hold the answers that she’s been looking for all along.

Director Kenji Kamiyama is better known for directing/producing many dark and complex sci-fi stories, including but not limited to Ghost in a Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Blood: The Last Vampire and Eden of the East. So, Napping Princess (known as Ancien and the Magic Tablet in Japan) is a stark new direction compared to most of his work. The movie was inspired by the director’s need to create something that he would want his daughter to see, and like a father creating a story from scratch as he tries to settle his little girl into bed, the dreams are bursting with imagination, big set-pieces and colourful characters.

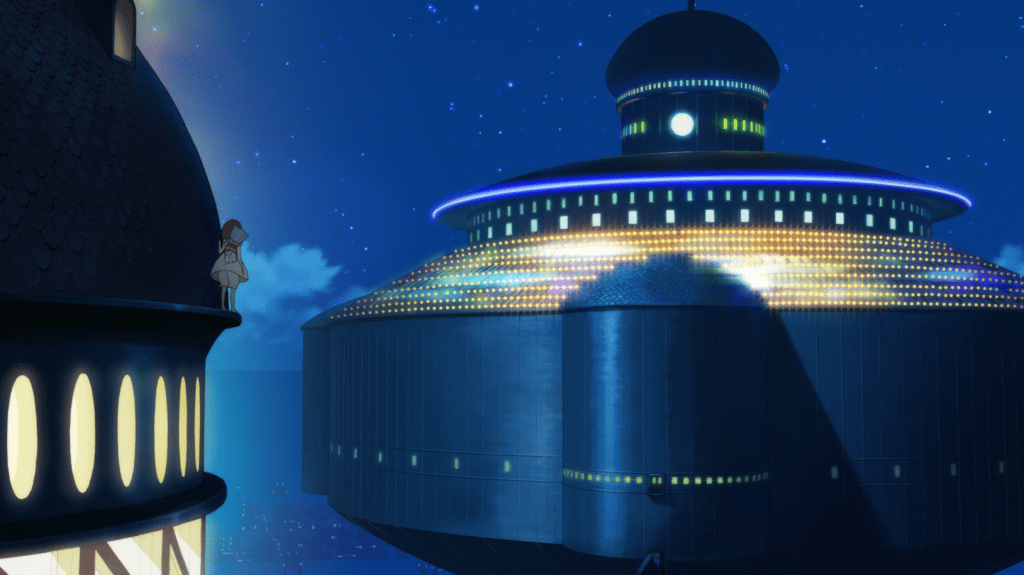

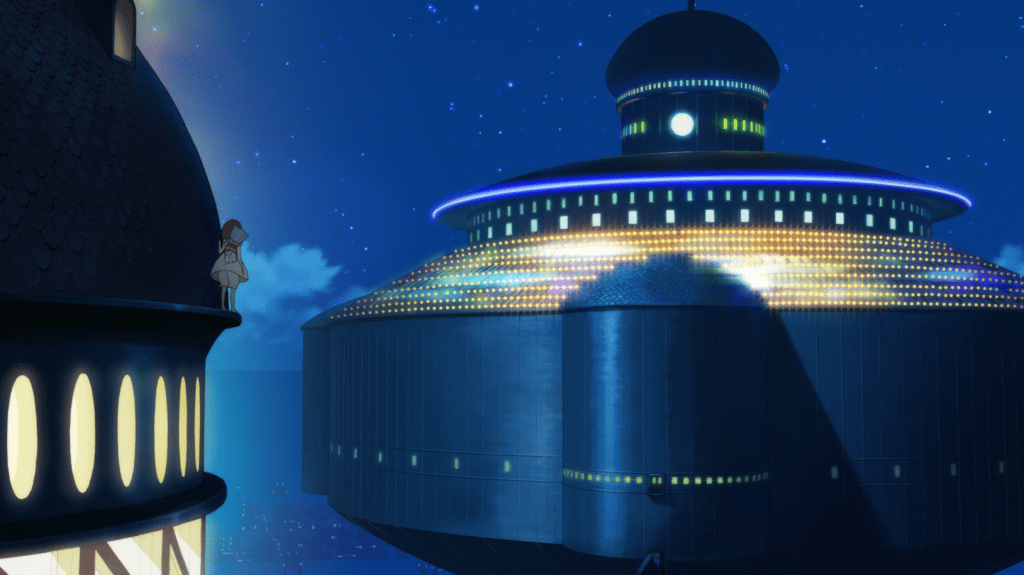

The film opens up with the dream world known as ‘Heartland’ in a pulse-racing beginning of a young girl ready to fight monsters and save her country until we’re thrust into the real world where the story actually takes place and said girl is nothing more than a high school student with minimal ambition. Napping Princess likes to play with expectations from the get-go, and as our heroine sleeps at random intervals, we’re dropped into the magical realm with little to no warning half the time. The director especially loves to throw the audience for a loop when the dream realm and real life start to bleed into each other, and, knowing Kenji Kamiyama’s work, nothing is as straightforward as it seems, with many clever double meanings in Kokone’s dreams hiding in plain sight, ready to be uncovered. This seems like a way to draw in an audience that is not just his daughter’s age but also his usual fans who love to see his more mature work; however, the overlap between dreams and reality isn’t as fully fleshed out as it could be. There are a few crafty twists involving Kokone’s mother and how her talent links to the dream world, but when it comes to the actual climax, where we jump from one gigantic battle to a life-or-death real-life situation, you struggle to see how one translates into the other without giant leaps in logic or ‘magic’ to wave it off. The pacing is also very bumpy; too slow in places and too fast in others; this in part can be explained by a father’s need to tell an exciting story to keep his daughter happy and that the nature of said ‘dreams’ don’t need to follow a set structure. But the film would have benefited from another few re-writes or editing to help make the journey flow better and the transition from the dreams to reality in the climax feels like one grand finale rather than two different experiences.

Considering that Kenji Kamiyama wrote the movie for his daughter, it’s not surprising that the film has a heavy focus on father-daughter relationships, however it’s marred slightly in that our protagonist Kokone is the least developed character in the film. The dreams revolve around her and she pushes the plot but personality wise, aside from being very tired all the time, she comes across as a self-insert, presumably to help other girls to feel like they’re part of the journey. The effect of this however is that the story, isn’t really ABOUT her, she’s the catalyst but the real story is about her parents and what happened before she was born, and they’re the ones given the arc and emotionally satisfying conclusion.

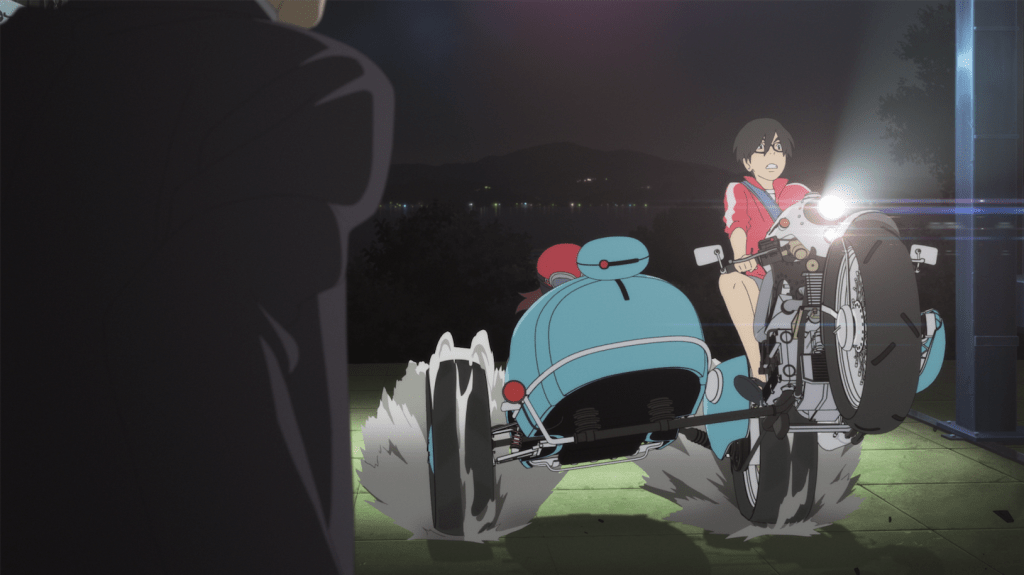

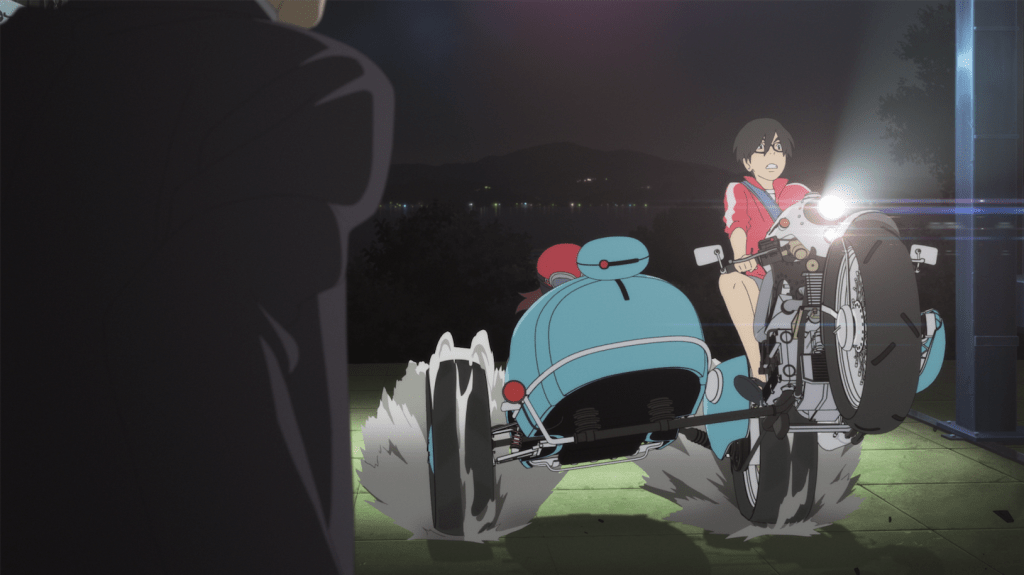

Animated films by nature have a much larger budget, and therefore giving feedback on it can be a little redundant, however whilst the majority of Napping Princess is pretty to look at, the 3D is glaringly poorer quality compared to the rest of the film. It’s badly implemented in places, especially when it comes to the transforming bike that appears frequently throughout the story. On the other hand there’s still plenty to admire design-wise: the colossus monster in Kokone’s dreams looks like something out of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and the transforming robot-bike that plays a large part in the story also looks very similar to Betamax in Big Hero 6 – the latter shouldn’t come as a surprise considering that Betamax’s designer (Shigeto Koyama) is also the mechanical designer for Napping Princess too.

Napping Princess is the innocent side of Kenji Kamiyama’s imagination run wild, so it’s full of outlandish worlds and fun characters, but falls a little flat in the logic and philosophical side that older anime fans may find underwhelming but younger ones won’t even see because they’ll be enjoying the ride too much. A family film for sure; it’s no Studio Ghibli or Pixar but it’s an enjoyable ride to experience in cinemas this summer.

Napping Princess is in selected cinemas for one day only on 16th August, by Anime LTD. Purchase your tickets here.

Continue reading...

Director Kenji Kamiyama is better known for directing/producing many dark and complex sci-fi stories, including but not limited to Ghost in a Shell: Stand Alone Complex, Blood: The Last Vampire and Eden of the East. So, Napping Princess (known as Ancien and the Magic Tablet in Japan) is a stark new direction compared to most of his work. The movie was inspired by the director’s need to create something that he would want his daughter to see, and like a father creating a story from scratch as he tries to settle his little girl into bed, the dreams are bursting with imagination, big set-pieces and colourful characters.

The film opens up with the dream world known as ‘Heartland’ in a pulse-racing beginning of a young girl ready to fight monsters and save her country until we’re thrust into the real world where the story actually takes place and said girl is nothing more than a high school student with minimal ambition. Napping Princess likes to play with expectations from the get-go, and as our heroine sleeps at random intervals, we’re dropped into the magical realm with little to no warning half the time. The director especially loves to throw the audience for a loop when the dream realm and real life start to bleed into each other, and, knowing Kenji Kamiyama’s work, nothing is as straightforward as it seems, with many clever double meanings in Kokone’s dreams hiding in plain sight, ready to be uncovered. This seems like a way to draw in an audience that is not just his daughter’s age but also his usual fans who love to see his more mature work; however, the overlap between dreams and reality isn’t as fully fleshed out as it could be. There are a few crafty twists involving Kokone’s mother and how her talent links to the dream world, but when it comes to the actual climax, where we jump from one gigantic battle to a life-or-death real-life situation, you struggle to see how one translates into the other without giant leaps in logic or ‘magic’ to wave it off. The pacing is also very bumpy; too slow in places and too fast in others; this in part can be explained by a father’s need to tell an exciting story to keep his daughter happy and that the nature of said ‘dreams’ don’t need to follow a set structure. But the film would have benefited from another few re-writes or editing to help make the journey flow better and the transition from the dreams to reality in the climax feels like one grand finale rather than two different experiences.

Considering that Kenji Kamiyama wrote the movie for his daughter, it’s not surprising that the film has a heavy focus on father-daughter relationships, however it’s marred slightly in that our protagonist Kokone is the least developed character in the film. The dreams revolve around her and she pushes the plot but personality wise, aside from being very tired all the time, she comes across as a self-insert, presumably to help other girls to feel like they’re part of the journey. The effect of this however is that the story, isn’t really ABOUT her, she’s the catalyst but the real story is about her parents and what happened before she was born, and they’re the ones given the arc and emotionally satisfying conclusion.

Animated films by nature have a much larger budget, and therefore giving feedback on it can be a little redundant, however whilst the majority of Napping Princess is pretty to look at, the 3D is glaringly poorer quality compared to the rest of the film. It’s badly implemented in places, especially when it comes to the transforming bike that appears frequently throughout the story. On the other hand there’s still plenty to admire design-wise: the colossus monster in Kokone’s dreams looks like something out of Neon Genesis Evangelion, and the transforming robot-bike that plays a large part in the story also looks very similar to Betamax in Big Hero 6 – the latter shouldn’t come as a surprise considering that Betamax’s designer (Shigeto Koyama) is also the mechanical designer for Napping Princess too.

Napping Princess is the innocent side of Kenji Kamiyama’s imagination run wild, so it’s full of outlandish worlds and fun characters, but falls a little flat in the logic and philosophical side that older anime fans may find underwhelming but younger ones won’t even see because they’ll be enjoying the ride too much. A family film for sure; it’s no Studio Ghibli or Pixar but it’s an enjoyable ride to experience in cinemas this summer.

Napping Princess is in selected cinemas for one day only on 16th August, by Anime LTD. Purchase your tickets here.

Continue reading...